Olympians

Chris Wardlaw

Much to his own surprise Chris ‘Rab’ Wardlaw, 47 years after balancing being a full-time teaching fellow and a full-time long-distance runner competing at the 1976 Olympics, is still striving to make an impact in the Australian education system.

Athletics

Montreal 1976, Moscow 1980

“I’m supposed to be retired. I’ve had three retirements!” he laughs.

“But I have always come back. Education has been my career forever.”

Following his retirement from the Athletics Australia board in 2022 Chris, or ‘Rab’ as he is called in the athletics community and by his grandkids, is the current Chair of the Victorian Curriculum and Assessment Authority and Deputy Chair of the Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership.

“They keep me very busy. I’m hoping to become more retired [over time], that’s the plan.”

The Athletics Australia life member and long-time running coach has never strayed far from his love of sport or the values of Olympism. You can still find the 72-year-old going for a run in Melbourne.

“I run everyday. I’m not injured. A few of my colleagues can’t run, so I feel very privileged that I can still.

Having a history of running 180-200km per week would eventually make some people eager to choose a different form of physical activity, but there’s no denying Rab still loves it.

A keen interest in films and music keeps him well-rounded, as does his wife Carmel and four kids Kerry, Ella, Christopher and Brendan.

The Wardlaw’s are a well-travelled family. Rab, Carmel and their youngest Ella lived in Hong Kong from 2002-2009. Ella’s gone on to London to work as a lawyer and Christopher is a teacher in Costa Rica.

Their fascinating time in Hong Kong came about when someone reached out to Rab with an opportunity, and the city has turned into their second home.

“I was recruited to be a secretary of education reform. Because I was in bureaucracy, their English was better than mine. I actually started having my grammar corrected.”

“But they also knew I had an Olympic background and was the head coach of the Sydney 2000 Australian Athletics Olympic Team. So I got on the Sports Committee of Hong Kong and was part of the lead in to the Beijing 2008 Olympics.”

The role he cherishes most was being a head coach at Sydney 2000. Rab had to pinch himself for it to sink in.

“That was just an absolute phenomenal experience, working with all the coaches. Particularly working with Cathy Freeman and John Coates.

“I was responsible for each track and field athlete in a way, but I worked very closely with Catherine’s coach Peter Fortune.

“[The 400m final] was an incredible experience. The whole world watched it. They’re things that stay with you forever.

“She’s still a very good friend, we meet up for walks.”

His career in education, specialising in curriculum policy, assessment policy and the professional development of teachers, was successfully navigated around his Olympic preparation, performance and recovery.

All of Rab’s employers offered tremendous support over the years, and his career-highlight of making the Olympic final in the 10,000m and the marathon at Montreal 1976 may not have been possible without it. It enabled him stick-up for all Aussie athletes to be allowed to compete at Moscow 1980.

“I took about three months leave, which included a bit of holidays, when I was teaching full-time and went to Moscow in 1980.

“Then when I was an executive in 2000 I was allowed to work full-time on the 2000 Olympics. It goes a long way and it’s the sort of thing we need for athletes nowadays.

Throughout his day-to-day life Rab is constantly getting friendly reminders of a special connectedness he feels to Olympians and the Olympic movement.

“I’m sure a lot of my career development has been assisted by the fact that I am an Olympian, and people respect it. Not just in sport, Olympism goes across anything that has the pursuit of excellence.

“The coaching I did in track and field is interrelated with the teaching of teachers.”

My training partners at the time, such as Rob de Castella and Gerard Barrett and a whole heap of others remain great friends. I find it a really valuable part of my life.

Olympians

Lee Zahner

It’s been a little over 20 years since Lee retired from playing beach volleyball, but he can very clearly recall what it feels like to be in a tournament alongside his Olympic volleyball partner and best mate Julien Prosser.

Beach Volleyball

Atlanta 1996, Sydney 2000

“I have these vivid dreams that I’m at a tournament and we’ve got to compete the next day. I miss it that much,” Lee said.

But then his focus quickly shifts to his wife Jaye, their kids Ziggy (8), Romy (20 months) and a property management virtual assistant tool that is rapidly evolving.

They are in a property technology (PropTech) company called Trulet, founded in 2017, which boasts an artificial intelligence machine learning chatbot to assist property managers and tenants.

“Trudy is our AI chatbot. It’s Siri for property management. Any issue for a renter or landlord can be answered by Trudy in seconds.”

While the technology side of building the chatbot isn’t Lee or Jaye’s forte, they’re both in their element when it comes to generating interest in the potential of the chatbot.

“Introducing people to the opportunity to invest in a new product is our forte.

They have been going through a pivotal time to close 2022 and open 2023, with the launch of a global Trulet campaign. Prior to getting going with the company six years ago, Lee’s career had been in property-related developments.

“It’s always been a property focused career for me after my beach volleyball career because it’s what I’ve known and really enjoy. My whole family has evolved from it.”

His parents were keen property developers in Queensland back when Lee was on the volleyball tour. The business they ran had them involved in land subdivisions, town house projects, small density buildings and more – and they found the time to travel overseas to watch Lee and Julien compete.

Lee’s mum was fighting cancer when he competed at Sydney 2000, and in 2002 he decided to cut his volleyball career short to spend more time with his family in difficult times.

“Mum was quite sick and she passed away in 2004. After that it was kind of a rebuilding phase for my family. I’ve got an older brother. My father was obviously a bit displaced. I moved in with him to get through a bit of a hard time. We got through it and we’re all still positive. Mum was extremely positive.”

“We pushed on. Dad was a town planner and had a very successful town planning surveyor business in Brisbane. We built a successful property development business together and did a lot of projects.

“That evolved into me starting a real estate business as well, specifically targeting for investor markets. It sort of grew a little bit with my partner at the time and we were selling a lot of off the plan units, land subdivisions and house and land packages for other developers. The real estate business became a bit of a monster. I concentrated on that up until 2017.”

At which point Lee’s wife and kids spent a week in Noosa, and when they were returning to Brisbane they shared a life-changing moment.

“Driving back to Brisbane in the traffic on a Sunday afternoon we just looked at each other and laughed and said ‘What are we doing?’

‘What are we going back to Brisbane for?’”

“We decided to sell everything up in Brisbane and move to the Sunshine Coast.”

When recalling his beach volleyball memories, too many to fit here, it’s easy to see why Lee thoroughly enjoyed competing all over the world.

“The camaraderie I gained from all these other players from different countries was just unbelievable. We still talk today. The WhatsApp group goes off when there’s a player’s birthday. That’s lasted through 20-odd years since I left. I cherish that part of the experience and I am so very grateful to have had it with Julien, we were like brothers.

“Even though there wasn’t a lot of money in beach volleyball, you could make a great living. We were invited to Wimbledon every year, the Woodies would always leave us full access tickets. We ended up at the dining hall with the Woodies and heaps of other players.

“We’d go to LA (from Australia) and train at Manhattan Beach and then jump to Europe to make the jetlag and time zone adjustments easier.”

But there was nothing like home and the lure of competing in a home Olympics at Sydney 2000.

“It was amazing to be playing a home Olympics at Bondi Beach. We trained 6-7 days a week down at Manly beach.

“Leading up to it Julien had knee surgery a couple of months out. The first time we touched the ball after that was on centre court at Bondi a couple of days before the event, but that’s sport.

“Julien almost suggested I play with someone else but that was never going to happen, we were always going to do it together. I can’t express how proud and grateful I am to have played with Julien at that level.”

Olympians

Liz Hepple

A road cyclist at the 1988 Seoul Olympics, who also went on to represent Australia in triathlons, Liz Hepple still carries a strong association to the Olympic movement in her current role as Athlete Wellbeing and Engagement Advisor at the Queensland Academy of Sport (QAS).

Road Cycling

Seoul 1988

Everyday she is committed to giving athletes of today a helping hand to navigate the complex nature of juggling family, friends, relationships, career interests and hobbies with training and competition.

Liz has noticed, the challenge of being an elite sportsperson often goes unnoticed when it appears an athlete has had a dream run to the top.

“When you see someone that gets on the podium at an Olympic Games, it hasn’t been all smooth sailing for those athletes. There’s been really devastating times and things they’ve had to bounce back from, resetting of their goals, starting training again and finding more motivation to get to the Olympics,” Liz said.

“Knowing and understanding that helps athletes deal with feelings of disappointment. Having been an Olympian you know what it’s like to go through all of that.”

Her passion also extends to helping sports people give back to the community by sharing their stories of resilience and goal setting to the next generation.

That includes encouraging Olympians to participate in training sessions of the Australian Olympic Committee’s schools program called Olympics Unleashed, which started on a smaller scale at the QAS.

Liz retired from road cycling following the Olympics but jumped straight into triathlons for the next three years, representing Australia at the World Championships and Commonwealth Games, living overseas for most of it.

Once she retired from elite sport in 1991 Liz started a family, had two kids (Jack, 30 and Bridget, 28) and became a cycling coach for 14 years before moving into the athlete career, education and wellbeing space that she’s in now.

In the same year Liz competed at Seoul 1988; she achieved what she describes as the highlight of her career, finishing the Tour de France on the podium in third place.

Her preparation for Seoul was strong and enjoyable, but Liz hoped for a better result than finishing 22nd in the road race.

“We had a good preparation for it. I didn’t have any major crashes that year. I did have a serious back injury from a crash the year before but lucky there was none of that in 1988.

“With road cycling anything can happen. You’re just happy to be selected [for the Olympic Team] and to arrive at the start of the race unscathed.

“The slight disappointment for me at the Olympics was that the course was relatively easy. It was quite flat and lends itself to a bunch sprint finish. I wasn’t a great bunch sprinter, I was more of a mountain climber.

“We tried very hard to set up a breakaway and get away but it never happened because the course didn’t lend itself to that.

Attending the Opening Ceremony is her favourite Olympic memory, but it very nearly could have been meeting Steffi Graf, if Liz had found the courage to introduce herself at the dining room table.

“The Opening Ceremony was a standout because that was a really unexpected thrill to be marching in the stadium as an Olympian for the Olympic Games.

“The dining room is where you feel the scope of the international teams and the different sports represented. Superstars like Steffi Graf were sitting at our table.

“There probably was [an opportunity to meet her] but I was too shy,” she laughs.

“In retrospect I kick myself that I didn’t, I’m sure she would have been fine with it.”

Liz went to school in Toowoomba and has lived in Brisbane, where she is now, for most of her life. As a teenager who was enthusiastic about swimming, Liz remembers being fascinated by watching Shane Gould swim on TV at the Munich 1972 Olympics, but she would later develop a stronger passion for road cycling.

“I can’t say I always aspired to be an Olympian, but once I realised I had the opportunity to go to the Olympics, it put extra motivation around my training.”

Liz is ready to prepare athletes for the next home Olympic Games, Brisbane 2032, and has advice for anyone wanting to make that Australian Olympic Team.

“Take people with you on that journey so you’re not alone and you have support when you need it, it just makes it so much more meaningful.”

“It’s going to be hard. Anything that’s worth achieving is going to be hard so don’t get disheartened, don’t give up. Just keep going for it and pursue your dreams.

Olympians

Olympians IN Business

Unlocking the Business Potential of Athletes: Insights from Australian Olympians

Numerous athletes worldwide, including Australian Olympians, have managed to create successful business ventures by leveraging their personal brands and vast networks, in addition to achieving excellence in their respective sports. The potential to generate supplementary sources of income exists for every athlete, whether it involves establishing their own companies, securing lucrative sponsorships or pursuing professional opportunities aligned with their post-athletic career aspirations.

Jeff Plumb

Jemima Montag

Play On

Grant SMITH

Two Mates Brewing Pty Ltd

Alex BECK

Fast Track Physiotherapy

James Willett

Kerri Pottharst

The Athlete Story

Pat Mickan

Matt Hayes

Melissa WU

Katya Crema

HIP V. HYPE

Amber Halliday

She Thrives In Sport

Caroline Anderson

Performance Edge Psychology

Yvonne HILL

David barnes

Danielle scott

d a n i e l l e

Tyler martin

Natalie Burton

Shelley Oates-Wilding

I Ikaika Hawaii nonprofit

Lydia Lassila

ZONE by Lydia

2014 Sochi · 2018 Pyeongchang

Paul wade

Lee Bodimeade

Rhys Howden

Tropical Plant Rentals

Rachael lynch

Simon upton

Lucas mata

Bearded Mountain Products

Colleen Pearce

Shaun Boyle

The Yacht Club Australia

Sally Fitzgibbons

Olympians

Olympian To Coach

by Brittany Elmslie

Passing on the Torch: Olympians Thriving as Coaches

Having more female coaches in sport is important for several reasons. First, coaching really should reflect society and gender equality in the workplace, whether it is professional or volunteer roles. Gender equality in coaching is important because it helps to breakdown stereotypes that women are not capable of coaching at the highest level. This can inspire more girls and women to become involved in sports as athletes and coaches. Having more female coaches can also provide role models for young female athletes, who may otherwise struggle to find mentors and support in the sports world.

Another reason why having more female coaches in sport is important is that it can lead to better culture in organisations and better performance on the sports field. Female coaches often have a better understanding of the unique challenges that female athletes face along their journey. They can also provide a more positive and supporting environment for athletes to train and compete in.

In short, we have reached gender equality for athletes in global sports like the Olympic Games. Governments and sporting organisations need to show leadership to make sure there is more encouragement, support and opportunity for women to develop as coaches. It makes as much sense to me to have a coaching balance on the pool deck, trackside or river bank as it does to have equality on the field of play and in the boardroom.

Myriam FOX OLY

National Canoe Kayak Slalom Coach IOC Coaches Lifetime Achievement Award 2022 Paddle Australia Bronze medal K1, Atlanta 1996

Olympians

Janelle Pallister

Australian Swimming Team Coach

Seoul 1988

I initially learnt to swim, like most people, for water safety. However, as I got older my doctor suggested I increase my water activities to help strengthen my lungs as I suffered from asthma. This is where my love for the water truly developed. For me, what made me fall in love with swimming was my desire for progression.

I wanted to progress through the learn to swim levels as fast as I could, always wanting to improve and get better. I remember being in the junior squad lanes and peering over to the other side of the pool where the senior squad were training and thinking to myself, “I want to work hard so one day I can be over there swimming in those lanes, swimming as fast as those swimmers.”

You were clearly driven from a young age, when did you realise you were talented at swimming?

Initially, I started out as a breastroker around 10 years old but actually I won my first national age medal at the age of 15 in the 100-meter freestyle. By the age of 17 I had won four open Australian titles in the 400-meter, 800-meter, 1500-meter freestyle and the 400-meter Individual medley. As I matured as an athlete, I found the right events which challenged me. I loved training. I know many swimmers prefer to race over train but as a distance swimmer I really loved the challenge of finding my limits of how hard I could push myself in training.

When you were an athlete what did you perceive a coach to be?

I thought a coach was there to guide you, push you and tell you what you needed. I swam in an era where it was very much you were told what you were going to do and how you were going to do it, without any input allowed. We would just do what was being asked of us and we didn’t really get to know why we were doing it that way. Nowadays, the training process is more educational; providing the athlete with knowledge on how the training will benefit them. I expected my coaches to push me really hard, help me achieve my goals and provide mentorship. I still keep in contact with all of my coaches I swam with throughout my childhood, as well as career.

During your swimming career was coaching ever on your radar as a potential career path for the future?

To be honest, I didn’t want to be a coach. I was fortunate enough after the 1988 Olympics, Australian airlines, which is now Qantas, gave out four working scholarships to four different Olympic athletes and I was lucky enough to receive one of them. It was myself and three other male athletes who won the scholarships. Turns outs two of the four of us, myself and one other, went and worked for Australian airlines, the other two were on more of a sponsorship arrangement and didn’t have to work to receive the funding. It was also discovered by one of the female supervisors that I was receiving $10,000 less than the other three athletes; and I was the one who was actually working as an air hostess. This kind lady took the time to fight for me to be awarded the same level of funding as the men; a gesture which I’ll never forget and meant a lot to me. When I missed qualifying for the 1992 Olympic team, I was feeling disheartened. Back then a 22-year-old female swimmer was seen as old and usually at the point of moving on from swimming. I kept swimming. However, I found myself considering what career path will allow me to continue to travel but not cost me too much; so, I kept working for Australian Airlines. In 1993 when the flight attendant applications came out, I decided to apply and I got in. To me, this felt like the stars were aligning. I decided to take the job as a flight attendant and retire from swimming; a job which I loved and enjoyed for 15 years.

Initially, coaching wasn’t on your radar, what was the pivotal moment where it started to become a consideration for you?

I had always wanted to move to Queensland, and when my mother-in-law passed away, we were ready for a change and decided on moving to the Sunshine Coast. I was still working for Qantas but had received a redundancy offer. I was at a point where I need to figure out if I was going to continue with flight attending or not. I was sitting watching my kids do their learn to swim lesson when my friend, Libby, suggested I give learn to swim teaching a go. I knew I would love teaching kids to swim, so I gave it a go. Not long after, I was sitting watching my son in his mini squad class and was asked to fill in coaching because their assistant coach was away. I was hesitant to say yes because I didn’t have any squad level coaching credentials, but they were desperate for help for a few weeks while the assistant coach was away. A few weeks had passed and parents were asking if their kids were able to continue to be coached by me. I was once again hesitant and agreed to coaching the junior squads only. It was a snowball effect from there, the juniors improved and need to move up into the senior squad but wanted to be coached by me. In order to not hold anyone back, I always made sure I stayed on top of what they needed. I started to attend coaching conferences and my desire to coach kept on progressing. Eventually, the juniors I was coaching became state qualifiers, onto state medalists. From there, my squad continued to improve and grow in numbers of age national qualifiers. The biggest thing for me was giving back to the kids and seeing them evolve and succeed.

Although you clearly loved coaching, why do you feel you resisted a career in coaching for so long?

I internally fought myself for so long on whether or not I should be a coach. It wasn’t until I made my first junior Australian team as a coach in 2017, that I finally accepted my career in coaching. However, I qualified for that junior world championship team by default, because one of the male coaches was unable to attend. I also insisted to the head coach, my daughter Lani was to be placed into another coaching group even though I was her actual coach. It’s interesting, when it came to coaching my kids, I always encouraged them to train under another coach, but both my kids would complain until I would allow them to come back to my squad. I get emotional when I think about why I always insisted I wasn’t good enough to coach my own children. I guess, from my perspective, I felt the pressure and judgment from the dominant presence of male coaches in our sport. I developed different protection mechanisms over the years to protect myself from the toxic masculinity, even other male coaches see and experience themselves. In 2019, when I qualified for the junior world championship team on my own coaching merit, I was labelled to be the token female coach by a few male counterparts. It makes me sad when I think about how many female coaches, I know have had the same experience. Athletes and our organisations are losing out on so many great qualities females offer. We see things differently. I know just by looking at my athletes I intuitively know when something just isn’t quite right with them.

There is no denying the discrimination you have face could have deterred you from coaching, however has there been a North Star that gave you the hope to persevere?

There were several moments prior to 2017 where I really questioned my reason for coaching. I felt like I was figuratively, hitting my head against a brick wall at times, but then there are amazing coaches like Michael Bohl (Bohly) who head hunted me to be a part of his team. Bohly could have easily picked any coach in Australia, and he chose me. I was extremely thankful that he thought enough of me and wanted me to come and coach with him. There was definitely an element of imposter syndrome, but the stars were aligning and my husband was retiring from his service to the police force; for me, this coaching opportunity with Bohly on the Gold Coast really felt like ‘now or never’. I decided to take the leap of faith, and here we are.

How does coaching make you feel?

There are times where you grit your teeth and question how can I do this better for my athletes. How can I change my delivery or whatever it may be, to make the athlete better. I have done a lot of personal development and learning this past year. I took part in Swimming Australia’s Women’s leadership course, and there was a particular exercise we did that was so powerful; it resonated with me more than any other values-based exercise I had done in other courses previously. The exercise focused on knowing your values but then paying attention situations that frustrate you and creating the link to what personal value that situation was triggering within you. For me, it is when people aren’t showing attention, and I feel that as a lack of respect. Respect is one of my core values, and I was raised in era where listening and paying attention was a perceived indication of respect; when a coach speaks you listen. Whereas the youth of today are growing up in a completely different era. What the exercise taught me was, I was getting trigger by my value not theirs. The self-awareness has allowed me to counteract the feeling of personal attack you feel when you are triggered by something and still find a way to connect with the person although we may not share the same core values. Once I was able to reflect on how triggering situations were affecting my ability to connect with my athletes at times, I was able to acknowledge that it was my responsibility as a coach to continue to work on myself and be the best I can be.

What are other areas of self-development you have focused on?

Several months ago, Bohly sent me a link to a video of accomplished coach Melanie Marshall speaking about one of her biggest regrets in coaching, which she said was, “caring too much and getting too emotional about what other people thought”; Bohly was quick to add that I was doing exactly that. I feel the approach of caring too much of what others think of me was directly connected to my avoidance of conflict. I decided to start educating myself and began listening to podcasts on how conflict is actually a very healthy part of relationships; conflict only turns unproductive when emotions arise. Something I realised was conflict was triggering my emotions and I would take it personally rather than conflict just being a constructive part of any relationship. These are all things Bohly and I enjoy self-reflecting on and talking about regularly. For me as a coach, I feel the more I empower myself to be better, the more my athletes will do the same.

What does your coaching style say about you?

I’ll explain it in a way one of my young 12-year-old athletes in the past explained my coaching style to be; he said, “you’re firm but you’re fair.” This kid was one of the ones who added so much value as a person to my training squad and our team. I also like to think I am compassionate. I speak to my athlete in a positive manner; outlining and focusing on what it is they need to do rather than focus on the things they shouldn’t be doing. Constantly speaking in do’s; what they need to do.

I know you love your motivational quotes, what would your favourite quote be?

One that resonates with me profoundly, in multiple ways is; “It’s what you do in the dark, when no one is watching, is what counts.” I think where I am now is – I definitely haven’t accepted discrimination, I just have developed constructive ways of dealing with it. I believe the moment we accept discrimination, is the moment we stop fighting for the future female.

It’s what you do in the dark, when no one is watching, is what counts.

Olympians

Katrina Powell

Head Coach of the Australian Women’s Hockey team

Athens 2004, Sydney 2000, Atlanta 1996

I grew up in Canberra, and my family was and still are involved in the St Patricks Hockey Club (St Pat’s) there. My uncle was a bit younger than my dad, so he was still playing in first division in Canberra on grass when I was young. My grandparents and our entire family would go along to watch my uncle play.

My cousins would all be there, so we would all muck around playing and having a hit ourselves while watching; a full family affair.My eldest sister started to play hockey, so naturally I wanted to start playing too. My dad wasn’t overly happy with how the first hockey club we joined was being run so he developed a junior girl’s program for the St Pat’s club. Girls from surrounding schools joined us and we were able to form a team. It wasn’t long before our family’s whole weekend was consumed by hockey and we loved it.

What was it about hockey that kept you coming back for more?

It was the competition aspect. When I was young, I was quite introverted; the moment I stepped onto the hockey field, it felt like a performance where I could be someone else. I loved the competitive challenge of mastering the skill of hockey, it’s not an easy sport to play but I quickly realised it was something I was good at. As I grew older, I grew to love the team element of the sport. The travelling, being with teammates. A born introvert; all of a sudden because I was a part of a team, I felt this sense of belonging and it was a great place for me to be.

You were young when you made your first Australian team, how did your coaches help guide you?

As a junior my dad was heavily involved with all of the teams I played for, or it was a parent of one of the other girls, so often they were family friends of my families. I was technically still a junior when I first made my first Australian squad and Rick Charlesworth was my coach. The step up to being coached by Rick in a national squad setting compared to the volunteer coaching I had received at a club level in Canberra was a big eye-opener for me. There was an intimidation factor, as you can imagine. Rick certainly got the best out of me and I managed to get the best out of myself to become the best hockey player I could be; I really respect and appreciate Rick for helping me achieve this. Even though it was intimidating at the start, I learnt a lot. Your junior years are for learning how to play the game but also your roles and responsibilities within a team. As you progress, you begin to hone your craft and establish your role within a team, which for me was goal scoring.

Did you find you had to adjust yourself to receive that hard style of coaching?

I feel like I was ready for it. I wasn’t someone who needed constant reassuring, being selected was the only reassurance I needed. I received direct, factual and honest feedback; I saw it as information and data I could use to actually get better. There was no fluffy stuff around it, I was told when I was the teams worst performing striker. Statistically being told how many outcomes you get, early on in my career it was confronting at times, but I saw it as an opportunity to do something about. Knowing the standard that was going to get me selected and having that information before I wasn’t selected, I found to be much better than after I wasn’t selected. It is this type of honesty I bring to my athletes now, so no one ever feels blindsided by non-selection. It’s important for athletes to not only know their areas of improvement but also know the areas they bring to the team that are appreciated. I find as females we undervalue what we are good at due to being naturally gifted within that area, but then compare ourselves to others areas of strength. I believe in the importance of athletes knowing their strengths and what they need to bring to the team every day.

The qualities you now display in your coaching, was that always what you perceived a good coach to be?

Most definitely, and Rick is an amazing person with a lot of experience in different fields, he is a high performer, that’s just who he is. I viewed him as the person with all the answers, I feel most athletes view their coaches in that way, but the truth is we don’t have all the answers, no one does. As soon as someone thinks they have all the answers they’re in trouble. One thing Rick was great at was making sure athletes understood they were accountable for the decisions they made. He would always say to us he knew he had done his job well when he felt he didn’t need to turn up on competition day. We had all the tools to put together a great performance and we didn’t need him to execute. The passing on of knowledge and information and wanting the athletes to improve and be the best versions of themselves, that’s what a good coach does; I learnt that from Rick.

During your athletic career was there something you felt you lacked, which you now ensure is present within your coaching style for your athletes?

Intimidation isn’t a great way to start any relationship. In my mind, it is not the responsibility of the athlete to have to build the relationship, it’s the responsibility of the coach. For example, when an athlete first joins an Australian squad, I believe they have enough to have to process. Everything is new, there is a lot of information to take on, so the necessary relationship building should be driven by staff; in particularly the head coach. The athletes still hold the responsibility to be communicating the things that need to be communicated in order to create open, strong and supportive relationships. The role modelling and mentorship aspect of coaching is something I take very seriously. I haven’t changed my phone number for a long time, any of my past and present athletes know, anytime they need me all they have to do is pick up the phone.

How has this importance of relationship building between coaches and athletes evolved?

It’s a different era, coaching was seen quite differently when I was an athlete. There has been a significate shift in how coaches are seen being good and positive role models. I feel previously coaches were seen as just motivators, with only a singular approach to achieving results and that was through passion, regardless of the impact. However, the science of coaching has progressed as well as athletes’ expectation of coaching in a high-performance environment, and we need to continue to evolve with that. Personally, I feel the direction high performance coaching is heading will increase and create more opportunities for female coaches.

Take us through the process you went through when transitioning from an athlete into coaching.

As an introvert when I was young, I continued to tell myself the story that I was still an introvert. First of all, I had to recognise that I had changed and I wasn’t the shy introverted teenager anymore. Those opportunities I received as a senior player on the team; public speaking, media engagements, post-match interviews and my captaincy experience – made me realise I had built some strong skills outside of hockey. I had an overwhelming sense of needing and wanting to give back, and I felt coaching was the best way for me to do so. I felt I wasn’t ready to stop travelling, or stop representing Australia, the passion I had for playing for the Hockeyroos was still very much alive. I just physically couldn’t train or compete at the level required anymore. In my mind, it was an easy transition, I had completed my decade long athletic apprenticeship and to me coaching was the next step in journey. Something I was most proud of when I finished off my athletic career was, yes there were Olympic medals but I had gotten the best out of myself. Early on in my career I set the goal for myself to be the best hockey player I could be, which was beyond winning tournaments each year. The sense of pride I have from playing for the Hockeyroos is incredibly strong. It is now my desire to help others get the best out of themselves, for the to feel the same sense of pride and achieve the same thing I was able to.

Did the level of contentment you felt towards your own athletic career, help with your transition into a career in coaching?

Absolutely, but no matter what it is and when it is; injuries, retirement or mis selection – the knowing you have done everything you possibly can; nothing beats it. I remember sitting on the plane heading towards the Atlanta Olympics thinking to myself, there is no more I could have done or we could have done to make me more prepared than I am right now. The ‘no stone unturned mentality’ – that’s Rick (coach), he’s a perfectionist. Rick was big on not letting luck determine the outcome, you can be unlucky, but we were always working towards being three goals better than any other team and knowing we had done everything we could. I feel this translates into my approach to retirement as well, the only way I was going to be able to walk away from the high-performance environment feeling content is if I could say to myself, I had honestly done everything I could to get the most out of myself with what was provided for me; and I was able to do just that.

During your transition into coach was there a pivotal moment where you felt coaching might not be for you?

There are always going to be bad days, times when I’m tired and lacking the passion, drive and enthusiasm – same as when I was a player. It is that same enthusiasm for wanting to play for Australia, for the Hockeyroos, wanting to go to the Olympics; that purpose, that why, is the exact same reason why I coach. I feel a lot of gratitude towards being a coach, and each day I want to do my best for the Hockeyroos legacy; it’s what gets me out of bed each day. I love my job; I love working for the athletes, for hockey within Australia but also for the Olympic ideals and what those ideals mean for young women in particular. Sport shows young Women that they can follow their passion. I like to remind my athletes who may be struggling with their career transition, I still don’t know where my life is heading but I do know I am passionate about what I am doing right now, and that’s all that matters.

What does a tough day at the office look like for you?

It’s usually an athlete being hurt, injured, not selected; it’s tough because I know to them it feels like their world is crashing – it’s hard. Or it’s a result. It’s the quarter final at the Tokyo Olympics, being knocked out and sent on a flight home the next day; that’s soul crushing. As a young athlete I experienced two knee reconstructions, which were challenging, but something it showed me was you don’t get to fully appreciate the highest of highs, winning Olympic gold, until you have felt the lowest of lows.

How does coaching make you feel?

I feel Joy. I am an enthusiastic and energetic coach who cares about the individual athlete and their well-being but also challenges them to be the best version of themselves. Working in high-performance is challenging, but if you aren’t enjoying what you do, then why are you doing it? High-performance is about improving every day, so if that is not enjoyable or fun, go do something else. To me, being fit, being the best you can be, improving on your skills, showing you’re world class, travelling with the Hockeyroos – that’s fun!

Olympians

Maria Pekli

Judo Technical Lead, Combat Australia

Beijing 2008, Athens 2004, Sydney 2000

I come from Hungary and Judo is quite a big sport over there than it is in Australia. I started my sporting career there just by chance really, with one of the coaches from the local club came to my school to do a bit of a recruitment drive and most of my classmate we interested in something new so we all tried it out and then I stayed in the sport for the next 35 years.

Initially, it was just once or twice a week and then I became a competitor. I have always enjoyed the competitive side of Judo; it is something that always resonated with me.

What do you feel resonated the most?

Judo is a very complex sport, a lot of skill is required. However, you don’t have to be very tall and there are different weight divisions. I enjoy that it is an individual sport, it came down to me who was making the decisions on the mat; if I win or if I lose, it was my doing. I enjoyed the combat, I am the eldest of seven siblings, not that I fought my siblings, but I think that helped. Many members of my family tried Judo at some point. One of my sister’s was the Hungarian National Champion when three sisters were all in the same weight division; I progressed in the sport the furthest of the three of us, I guess I was the one who wanted to see where it would lead me if I stuck with it.

How long were you in the sport as an athlete?

My sporting career was quite long, I started in Hungary when I was 12/13 years old. I went to my first Olympic games for Hungary when I was 20 (Barcelona 1992), then Atlanta 1996 Olympic games. I then migrated to Australia and went to the 2000 Sydney Olympic Games, which is where I won a bronze medal; something that hadn’t happened for 36 years prior to that and we haven’t won another Olympic medal since my bronze in 2000. Athens in 2004 when I was 32, and then I retired. Me and my partner Daniel (Australian Senior National Coach for Judo) had a child together. Daniel couldn’t give away the sport, so I said, “Well if you’re still doing it then I’m going to do it to,” and we both ended up going to the Beijing Olympics in 2008, where I finished fifth as a 36-year-old mother. There aren’t many Women who have returned to Judo after having a child, mainly because it is not an easy thing to do. I am one of five Women who have been to five Olympic Games in the sport of Judo, something I am so proud of and I couldn’t have achieved if I didn’t return to the sport after giving birth to my child.

Did your mentality change once you became a mother?

The fifth place I fought for in Beijing actually feels more special to me than my bronze medal in Sydney, because it was a very different circumstance; I wasn’t just responsible for me anymore, we had our child and they have a very serious genetic condition too. At the time, he was a sick little boy and he still is, he has a metabolic disease that has no cure. In January 2020, he needed a kidney transplant and I gave him my kidney. The rest of his body is still fighting hard against his metabolic condition.

What was your relationship and experience like between you and your coaches throughout your career?

My first junior coach in Hungary was influential to me as they made Judo interesting and enjoyable. Once I made the Hungarian national team, I had a coach who was an older gentleman and his slogans and approach still stick with me today. When I moved to Australia, my partner also coached me and the club we joined was run by 8th Dan Blackbelt, Arthur Moorshead. Arthur created an environment to make athletes want to be there, he gave use independence and a key to the dojo so we could be there whenever we wanted to train. The dojo was a safe space for us to progress and he always advocated for us. We knew we could always rely on him, if we ever had any problem, we could always turn to him. Arthur was understanding, always listening, asking questions and offering solutions.

Did you find you took that same approach when you transitioned into coaching?

When I first transitioned into coaching from an athlete, I was coaching the Victorian State Team for quite a while. Being a small sport with limited funding, this wasn’t a paid position, it was a volunteered position. I am an accountant by profession, I used to work for Ernst and Young (EY) and got my job through the job opportunity program, they ran after the Sydney 2000 Olympics, which was amazing for someone like me who came from another country and English wasn’t my first language. Being part of the program meant I had to redo my studies, as it was a different profession to what I was doing in Hungary, but it was a great place to work and I was able to support myself working part-time while still training full-time. I feel the balance of study with sport is great for time management. I believe sport and study compliment each other even though you find some parents of athletes don’t agree. Athletes appeal to a lot of the big corporations; their athletic skill set is transferable, and they have the discipline to work at these corporate workplaces. When I retired from judo, I transition into a full-time position with EY and was there for a few years before starting a roll for the Judo Federation. I now run the National Judo program as well as the pathways program; I focus on the coordinating and strategic decision making for our sport.

You could have easily gone into the corporate world and chosen not to give back to the sport of Judo, but you didn’t, you remained connected in a volunteer coaching capacity while working full-time.

You could have easily gone into the corporate world and chosen not to give back to the sport of Judo, but you didn’t, you remained connected in a volunteer coaching capacity while working full-time. What drove your desire to continue to give back to your sport?

The love I have for the sport is what kept me coming back. I love helping people to become better at what they do. When I first transition into my role at the Judo Federation, Australia was ranking poorly on the international stage. We weren’t winning many fights and I really wanted to help change that. One of the board members and I, who was also a former coach of mine, started talking about how we could make the program better. At first, the role started with me doing a bit of consulting, but it quickly grew as there was so much to do, and so much to change. At that point, I had to make a decision if I was going to leave my professional career with EY and go full-time into helping my sport. I felt I could make a difference to Judo in this country and help athletes to become better, so I chose to change career paths and it grew from there into what I do now.

What was the driving force behind that vision you had for Judo in Australia?

I wanted to help athletes to have the same experiences that I had on the international stage. We have progressed a lot, when I first started, we only had one or two medals within the program, now we have ten. We had two girls finish in the top eight at the most recent World Championships, which the program hadn’t achieved since 2003. It is a long progress to get someone to that level in Judo, but we worked hard at it. Hopefully we will get an Olympic medal in Paris 2024, which hasn’t been done since my medal at Sydney 2000.

What are the key areas of impact and evident cultural shifts you’ve seen along this journey?

One of them is the pathway program we created, which starts at a cadet level and works all the way up to our senior level athletes. It’s a year-round program where we prescribe the training workload based on the different levels and outline what competitions they should be aiming for based on their level of experience. We used to have a system where the younger athletes would only go to two low level competitions a year. What we noticed was the athletes would compete at these competitions and believe this was the highest level they could achieve, so they would eventually leave the sport. The pathway program we have now is very intentional and provides a clear pathway to work towards competing at the World Championships, and we have seen better retention within our sport because of it. One big change we really advocated for was moving the focus away from competing at the Oceania Championships, which was not challenging our athletes; they were winning all the weight divisions, but we found it wasn’t translating to success at an Olympic level. We now compete within the Asian Championships, which is a much higher level of competition. I believed making this shift was within the best interest of the athletes, however I only had two people in the Australian Judo community who really supported this decision initially. But it paid off and in our first year competing at the Asian Championships we won three medals. I found every time we raised the bar; the athletes raised their standard.

Speak about the belief you had to have in the vision you had for the sport?

A lot of the state institutions were against it at first. I found clubs and state systems wanted to hold onto their athlete in fear of losing them, but this was detrimental of the athlete. I knew we had to work towards creating a centralised system if we were going to work towards Olympic success. The vision was a purposeful centralised training location for Judo and Tae kwon do, the concept now known as Combat Australia. We knew if our sports came together, we were going to be more powerful and received more support. Most of our categorised athletes are now training within this centralised system environment based in Melbourne, something I am very proud we were able to do for our sports. Unbelievably, the results spoke for themselves at the Birmingham 2022 Commonwealth Games, ten athletes came home with a medal, whereas the best performance we ever had before this at a Commonwealth Games was five medals. I am very proud of where we have come from, but it hasn’t been an easy journey. When people don’t share the same vision as you do, they challenge everything you do, which was exhausting.

What do you find most challenging about your sport?

We don’t receive a lot of funding, which I understand because we don’t have an Olympic gold medal so we can’t justify the higher funding. I see it like the chicken-and-egg scenario, people lack the belief we can get there and know we won’t have funding until we get there, but I know we just have to find a way and then we will have the funding we desperately need. I often hear the athletes complain about the sacrifices they have to make to do the sport of Judo, but I see it and have always seen it from a different perspective of investment rather than sacrifice. I see investing in low funding high performance sport the same way I see someone choosing to invest money into a university degree. The goal is the same, you want something at the other end. One is a gold medal and the other is a University Degree. You have to change the viewpoint, if people think they are giving up something the journey isn’t as satisfying compared to when you see it as an investment into yourself and your sport. Sacrifice has such a negative connotation attached to it, people see it as a loss of something, compared to the preconceived ideas of what it means to invest in something.

I was fully paid athlete when I lived in Hungary and then I moved to Australia where there was no funding in the sport of Judo, as well as no employment opportunities for athletes in Judo either. I learnt the hard way, but if you want to achieve something then you have to invest in it until you get to the top. My experience as a paid athlete to a non-funded athlete was interesting because I found I was a lot more determined to perform as a non-funded athlete. The feeling wasn’t the same, when I was paid, I felt I owed something to those paying me whereas when it was me investing in myself, I really felt the return on investment was much more satisfying.

Where do you envision your sport heading into Paris 2024 but also into the future?

We are building towards consistency in international performances across all levels and age groups. A legacy that I would love to leave the sport of Judo with is; once athletes have journeyed through the pathway program and are ready to finish their athletic career, they see transitioning into coaching or another role within the sport as an appealing way to make a living. I want athletes to believe there is a profession for them in this sport instead of feeling they need to leave and go become an accountant like I did. At the end of the day, sport is a business. I want Judo athletes to know if you structure it right, you can set up your own business within our sport. The vision is to have as many training centres as possible feeding into the centralised program centre, and I would love all athletes to walk out of their time training at the centralised centre with a coaching qualification; growing the sport but also inevitably begin to receive their return on investment into themselves and Judo.

Olympians

Sandy Brondello

Head Coach of the Australian Opals’ and

the New York Liberty in the WNBA

Athens 2004, Sydney 2000, Atlanta 1996, Seoul 1988

“I fell in love with basketball the first time I joined a team and played – at the age of nine. We lived outside the city on a farm, my Dad was a sugarcane farmer and my Mum couldn’t drive, so we relied on our friends to be able to get to training and games.”

There was a country team, which trained at another school nearby mine that my sister and her friends played for. One day the team was short on players; they asked me to play – and the rest is history. I loved it right from the beginning, but at the same time I was also doing track and field, which I was overlapping with basketball for some time. Track and Field, you’re by yourself, it was all on me; I was good at it but I knew I didn’t love it like I did basketball. I always had natural ability; I was physically strong from athletics but also from working on my dad’s farm, carrying pipes through the mud. I was a typical country girl.

What events did you do in track and field?

My specialty was high jump as well as the 100m, 200m and the relays. In year 7, I won the national championship for high jump at 12 years old. I actually didn’t really want to go to that tournament because I was a bit of a mummy’s girl and I didn’t want to get billeted out. Although it may not seem like it now in my 50s, I was a shy kid, and sport was great for my confidence because it was something I was naturally good at.The basketball court was my haven, it’s where my personality could shine; it wasn’t until later where I gained enough confidence to find my voice off the court. I believe everyone should have the opportunity to play sport, regardless of whether they are good at it or not, it holds so many great advantages.

Was it surreal for basketball to eventually turn into a career path for you?

I still pinch myself at times that I get to do something I love; it’s never been a job to me. Yes, I get paid to do it but to me basketball is my passion; I know not everyone has the privilege to say that. I retired from my athletic career when I was 36 years old, I’m now 54 and I’m just as passionate about basketball. One of the respected coaches in the WNBA, he only just retired from coaching at the age of 72; you can coach for as long as you can still do your job at a high level, which I think is cool.

17 years as an Australian Opal, what was that journey like?

I made my first Australian team at the age of 18 in 1987 and my first Olympic Games was Soul 1988 the following year. I went to four Olympics (Seoul 1988, Atlanta 1996, Sydney 2000, Athens 2004); we actually missed qualifying for Barcelona in 1992, so it should have been five Olympics. Back in those days, there were only eight teams that are able to qualify for the Olympics; there’s 12 spots now. The reigning Olympic gold medalist team and the host nation automatically took two of those eight spots. It came down to the last game, we needed to win but we lost by 4 points to former Czechoslovakia and missed qualifying. It was heartbreaking, qualifying for an Olympic spot for Australia; it’s what you train for as athletes.

The longevity of your career is an achievement in itself, was there a coach in your formative years who made a lasting impression on you as an athlete?

The one who really impacted me, still to this day, and I caught up with him at the most recent World Cup, Sport Australia Hall of Famer; Dr Adrian Hurley OAM. Adrian was the one who got me to the Australian Institiute of Sport (AIS). In 1985 he asked me to go to the AIS and five minutes before I was meant to leave, I decided I wasn’t ready to go, I didn’t want to leave my family and I wanted to finish year 12. I went to the AIS the following year in 1986, I remember my first session and Adrian told me he wanted me to be a point guard and I was like hell no, I’m not dribbling up the court, no way. The small country town girl in me couldn’t fathom being a point guard, but we got to work. He would get me on the squash court, and I would wear glasses that stopped you from seeing the ball and we’d work. Adrian was always someone who believed in me, more than I believed in myself. In my second year at the AIS, I worked closely with Phil Smyth AM, he was coaching the Men’s team but he would also do player development with me. Phil is the reason why I wore the number six during my career, I was in awe of him; starstruck. However, over the years, even once I moved into coaching Adrian continued to reach out and check in with how I was going, always uplifting me when I needed it. After we won the 2022 World Cup, we had a moment together and I thanked him for the impact he has had on me; I wanted him to know how much he helped me over the years. His words of encouragement mean so much to me; he’s been my biggest inspiration and mentor.

Has the impact Adrian had on you as an athlete helped shape the way you show up as a coach for your athletes?

Without a doubt! You never know the impact you can have on somebody’s life. Coaching is all about building relationships with the athletes, learning how they tick in order to get the best out of them, because everybody’s different. I played for a long time, I had a lot of great coaches throughout my career; in the end I’m not trying to coach like anyone else, I’m trying to be who I am. As a person, I know I perform my best in a positive environment, surround by good people. I don’t have time for negativity and entitlement. As an athlete I was always my own worst critic, my biggest strength was my work ethic and I was always doing something to be the best I could be.I see my role as a coach more as a servant leader, which suits my personality; always positive but then hard on my athletes when required but it comes from a place of belief in their potential. I want my athletes to play free, do their best and learn from their mistakes, not play to please me. To me, that is more fulfilling.

You have a great sense of knowing what works best for you, how were you able to form that level of self-awareness while playing in a team environment for such a long period of time?

I loved playing basketball and the greatest honor to me was playing for Australia in the World Cups and the Olympics. In a team sport you have to play many different roles, in 1988 I did not play one minute of court time and this is how I relate back to my athletes; of course, I wanted to be on the court playing but it was more about the best interest of the team. It doesn’t have to be a poor me thing, my experience during that situation actually inspired me to work harder. I was able to make the connection that if I wanted court time, I needed to be better. The following year in 1989, I got into the rotation; I realised I was able to control my controllables, acknowledging what I needed to do in order to gain more court time. Like anything, the more experience you gain the better you get; same goes with the mental aspect of sport, you understand the game better. As a kid, although I came from a small country town, I had great coaches; Carol Lynch and Mel Mcconley, both coaches from Mackay. But in comparison to players who grew up in the big cities, I hardly trained, my dad was a sugarcane farmer and my Mum couldn’t drive, which meant one day a week I made it to the city for training and the rest was self-driven in my backyard. This is where I discovered the mental game in staying confident. I learnt my biggest strength was my offensive game, I could score. Defensively, I was a smart player but it was an area I always worked on.

Was there a pivotal time during you career, which challenged you and your mental game?

I played during the Atlanta Olympics with a navicular stress fracture. During a lead up game, I injured my shoulder, was out for six weeks so I ran, but then developed a stress fracture. I played in a lot of pain and it was disruptive but it was one of those experiences where the mental toughness helped me get through it. I used my passion for the game to overcome the adversity I faced, it’s all part of the journey. Sydney 2000 was probably my favourite Olympics, I was in the starting five, it was a home Olympics in front of my family and we win won a silver medal. The following Olympic cycle leading into Athens 2004 I was more of a mentor within the team, didn’t play as much and knew my body was breaking down and it was time to stop playing. By this point I knew I wanted to coach and I was lucky to enter the Women’s National Basketball Association (WNBA) the following year in 2005; and here I am.

You say you knew you wanted to coach, when was that lightbulb moment for you?

I was in a relationship with my now husband who is a coach, and when you’re living with someone who is a coach you see what goes into the planning each and every day. I realised there’s nothing else I would want to do; my whole life has revolved around basketball. I don’t feel like it’s my identity, but it probably is my identity; it’s all I know. It has been at the top of my priorities till my kids came along. My husband jokes he has never managed to trump basketball on my priority list; he’s probably correct.

When did you know it was time to transition into coaching?

I just knew it was time when I started to get injured. My body was tired, it was becoming a grind. I used to play all year round, I do the WNBA season into the European season; playing over 100 games a year, it was wearing me down. 36 years old at the Athens Olympics, I was old. I felt content with everything I had achieved as an athlete, I was the best I could be and I now wanted to coach at the highest level. I was fortunate enough to have a few female coaches during my career; Jenny Cheesman, Bronwyn Marshall, Anne Donovan, Nancy Lieberman Klein and Jan Sterling for the last four years of my career. I knew I wanted to coach and I backed myself. Lucky enough I was in a great situation where I got an opportunity straight away, and it’s the main reason why I am where I am today. I’m a former player, coaching in the best league in the world. This year we had nine of the 12 coaching opportunities filled by females and six of them are former players; and females are getting these coaching jobs on merit not because we are female.

Why do you think basketball has great conversion and retention of former players into coaches?

In Australia, we are making progress but could be doing more in this space. In the United States they are fantastic stepping stones for former athletes to transition into coaching. The WNBA has a rule that if one of your coaching staff is a former player then your third assistant coach can also sit on the bench. Only two teams last season didn’t have a former player sitting on their bench; I feel this season every team will make the most of the opportunity, which is great for the sport. The WNBA also do a great job at giving internships to help current players gain experience and explore career opportunities while they are still playing.

You managed to have two beautiful children while establishing yourself as a coach, how did you manage it all?

I retired in 2004 when I was 36 and gave birth to my first child, in February 2007. My Husband and I were fortunate enough to be coaching together in San Antonio while navigating parenthood together. The team allowed me to travel and continue to do what I loved with our son. Then in 2010, I was offered my first head coaching job in San Antonio while I was pregnant with our second child and I took the job. In hindsight, I probably shouldn’t have taken the job, but I gave birth during the season and was back coaching eight days later and then travelled the rest of the season with two children; I was breastfeeding and everything, it’s a blur, I can’t remember much of that period of time. It’s because of that experience I now give the advice to young coaches to not jump at an opportunity unless it feels right. I always say, the lesson in the experience is always positive.

What’s the best piece of advice you’ve ever received?

Keep believing in yourself, learning and growing. Surround yourself with people you trust and who care about you.

Olympians

Olympians

In The Community

Beyond the Podium: Olympians Making a Difference in Their Communities

Athletics

My name is Nina Kennedy, and I’m a full-time athlete in the event of Pole Vault. The Olympics Unleashed program benefits everyone involved. The kids get something out of it, and the Olympians sharing their stories also benefit. I’ve been involved in several Olympics Unleashed tours and talks. I have travelled up to the East Kimberly in Western Australia twice, visited schools in Perth’s metropolitan area, and participated in an Olympics Unleashed TV session.

Travelling up to the East Kimberly was an experience I’ll cherish. Visiting schools in remote communities was terrific. The kids were excited to have visitors, listen to our Olympic stories, and have new people to play games with. I could tell how intrigued and inspired the kids were by how they sat and listened without taking their eyes off me while I shared my journey of being an elite athlete for Australia. I shared photos and videos, success stories, and some failures and difficulties I’ve faced. I emphasised how important it is to show resilience and dream big in whatever they want to do. I also taught the kids how to do some simple goal-setting by using examples from my career. I was just as intrigued and excited as the kids were. The kids taught me some words in the Indigenous language they use and shared their stories with me. Olympics Unleashed is a great program; everyone involved leaves feeling inspired and grateful. This program is an excellent way for athletes to give back; giving back is an essential and special part of being an elite athlete.

Rowing

To “place sport at the service of the harmonious development of humankind” that is our mission as according to the Olympic charter. Helping others grow is at the core of the Olympic movement, a notion embodied in the Olympics Unleashed program. I have been lucky enough to be a part of this program for the last 3.5 years, speaking to children across New South Wales. They have been from different regions, socio-economic levels, cultural backgrounds and abilities, all connecting over the same stories.

It is one thing to inspire from afar, and quite another to stand in the same room and connect with these kids on their passions, be they sport or otherwise. This is one of the great parts of the program, that we are able to bring our “whole selves” to the talk, sharing all the parts of us that have led to the person they saw on the podium, and the path to the person we are today.

There is a genuine connection with the audience only possible when we tell our authentic stories, as they see little bits of themselves in the stories. A positive feedback loop starts to happen if we create the space to listen to their stories as well, bouncing perspectives back and forth. I always come away both exhausted and full of energy from these talks.

There are so many reasons I have been grateful to be a part of this program. Being able to reach these kids at such a formative age, and help to bust stereotypes around what they can and cannot achieve. Answering hard questions, often helping clarify my own thoughts on some topics. Representing the Neurodiverse community. Starting conversations. Making a difference for these adults of tomorrow.

Canoe Sprint

Every time I visit a school as a presenter I think back to the visits I had from two Olympians when I was at school – Alana Quade (nee Boyd) and Melanie Wright (nee Schlanger). Their stories and words of encouragement helped change the way I approached my goals and proved to me that with hard work and persistence, anything is possible. Fast forward 14 years and I feel very privileged to now be in their shoes and have the opportunity to potentially have a similar impact on our next generation.

When I first started presenting I was particularly worried about how I would connect with a group of kids who may not be interested in sport, but I think the real strength of this program is its ability to resonate with kids from all walks of life. Seeing their smiles and hearing what their goals are, both in and out of sport, is incredibly rewarding and gives me a real sense of pride and purpose. So, as the runway to the Brisbane 2032 Games begins, I can’t wait to see the impact this program can continue to have within our communities.

Rowing

My name is Caitlin Cronin, and I am an Olympic Bronze Medallist from the Tokyo 2020 Olympics in the sport of rowing. I am privileged to have been involved in the Olympics Unleashed program for just over a year now, sharing my story with many schools around both Queensland and NSW. I am incredibly proud to be part of the program; inspiring students to set goals, build resilience and create the best versions of themselves in whatever they choose to do in life. My journey to becoming an Olympic Medallist was far from smooth sailing. Missed selection, COVID postponement and serious injury are just a few of the speedbumps I overcame along the way. Through these setbacks I developed resilience and perseverance, and they shaped me into the athlete and person I am today. I think it’s very important for the kids to understand that it’s okay to fall short of goals and that they should get back up and have another go! I aim to make my story relatable for the kids and remind them that I too was once a primary school student who wasn’t sure what they wanted to do! I definitely wasn’t the most talented rower when I first started rowing in grade 8, in fact I was in the 3rd crew, and we didn’t even make the final at the Head of the River! But I enjoyed working hard and challenging myself and with years of dedication managed to achieve something pretty cool. I hope to help the kids understand that just because you aren’t the person with the most natural talent doesn’t mean you can’t achieve great things.

A highlight of my time with Olympics Unleashed so far is a tour with CLaW (Centre for Learning and Well-being) in Far North Queensland. Over five days I presented to a different regional school each day, traversing hundreds of kilometres of dirt road between each school. Whilst there is not much water for a rowing boat in regional Queensland, I hope I was able to inspire students to dream big, work hard and be resilient as they work to achieve their goals. Sport is such a good way to create connection in rural communities and to create healthy habits and a good state of mind. Another highlight was a recent visit to Budawang Special School. The excitement of the students was infectious, and I loved the opportunity to share my medal with them and challenge them to a running race. The pride and joy on the faces of the children reminds me just how special it is to have the opportunity to represent your country on the world stage and also to be able to share the experience.

For me personally, being part of Olympics Unleashed is incredibly rewarding and an opportunity I am very grateful for. If I can inspire even one kid to get out there and have a go at something they love, set themselves a new goal or pick themselves up and have another try at something I consider that a big win. We have an amazing young generation and I hope to see some of them kicking goals at Brisbane 2032!

Olympians

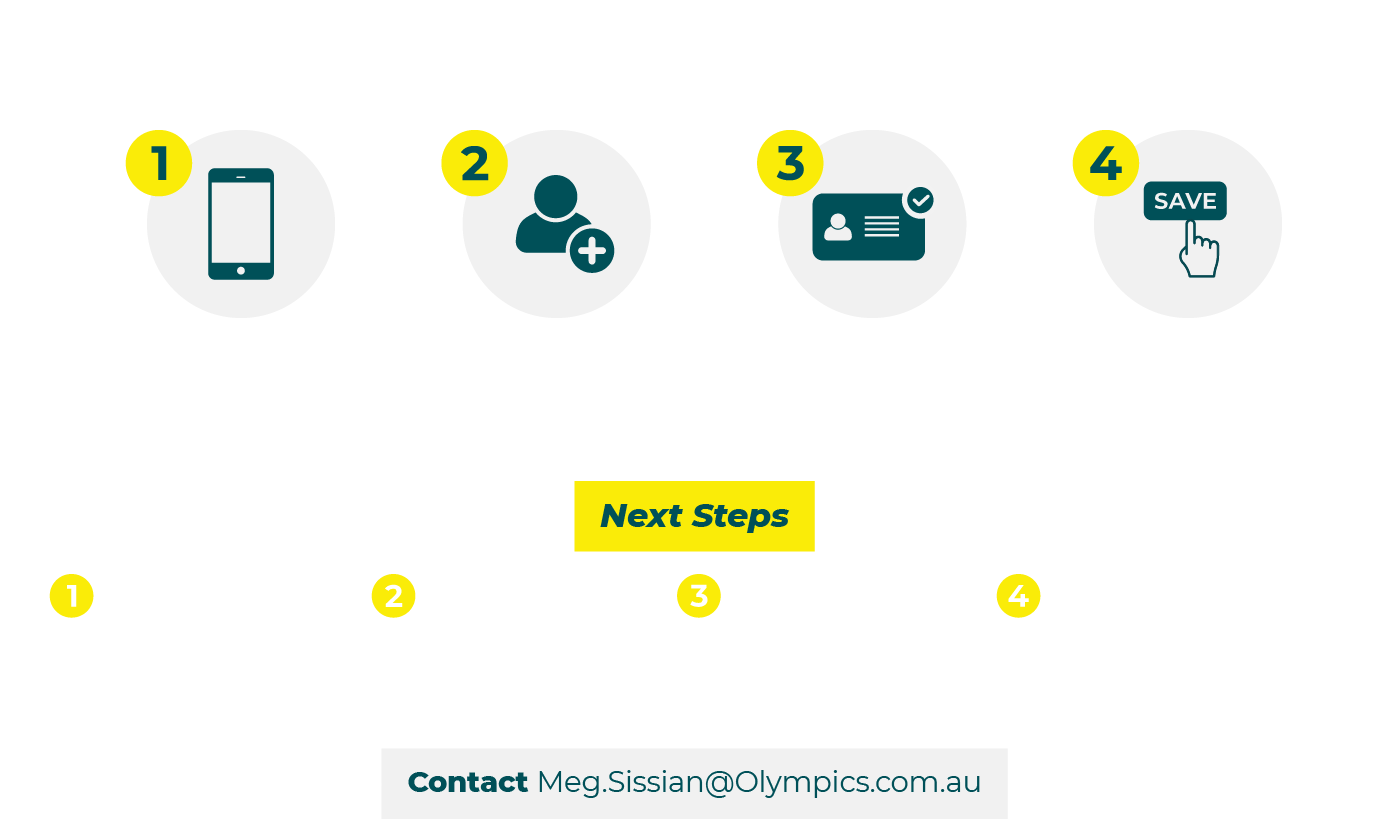

Stay Connected

The AOC recognises the importance, and greatly values staying connected with you as Olympians Whether it is sharing information about upcoming Olympians events, reunions, or community events and opportunities, we don’t want you to miss out on being involved in the things that matter to you.

The AOC makes every effort to maintain key contact information so we can stay connected. We understand that from time to time these details change, so please ensure you advise us of any change of details including email, mobile and address.

For all matters relating to the Olympic Team, the Olympian Opportunities program, the AOC engagement platform and general communication please contact:

Daniel Kowalski, Head of Olympian Services: daniel.kowalski@olympics.com.au

Meg Sissian, Olympian Liaison Manager: meg.sissian@olympics.com.au

Download from

the App Store

Download from

Google Play

We never forget our Olympians and would like to honour their passing in offering the Olympic Flag. The AOC would like to be notified on the passing of any Olympian. The Olympic flag is offered to the family to use at the Funeral / Celebration of Life in memory and honour of the Olympian’s achievements and can retain the flag. The family is automatically permitted to use the Olympic rings in a Funeral / Death Notice in any newspaper and on a plaque or headstone (if they so wish).

Please do not hesitate to contact the AOC on (02) 8436 2184 or via email: meg.sissian@olympics.com.au if you have any questions or require clarification.

Following an extensive consultation process with the presidents of the Olympians Clubs this year, the Australian Olympians Club/s is now the Australian Olympians Association (AOA) to align with the World Olympians Association (WOA).

Each state and territory’s AOA has a leading delegate who is responsible for the engagement and activities of the AOA in their respective states and territories.

For matters related to the AOA, including fundraising, social events and ways to be involved with the AOA.

AOA Co- Chairs: Louise Dobson (Hockey 1996, 2004) & David Culbert (Athletics 1988, 1992)

ACT

E: aoaact@olympics.com.au

NSW

E: aoansw@olympics.com.au

QLD

SA

E: aoatas@olympics.com.au

TAS

E: aoavic@olympics.com.au

WA

E: aoawa@olympics.com.au

Over 17,000 Olympians have registered for OLY and their Olympian.org email since November 2017, with an average of 200 new sign ups per month. Use the OLY letters on social media, your resume, business cards… in fact, anywhere you use your name. Over 1400 Australian Olympians have registered for OLY. If you haven’t yet registered, go to olympians.org.

Available only for Olympians, this is a great way to get yourself noticed in people’s inboxes – perfect for work or play. Register at olympians.org for your exclusive email address. PLUS… ww

As Olympians, you can also take advantage of the following IOC opportunities:

Create a profile on the IOC’s Athlete365 platform. Here, you can keep up to date with the latest Olympic news, find out about career opportunities, and more.

Further your education with a free short course on the Athlete Learning Gateway. accessible via Athlete365.

Natalie Cook - Beach Volleyball ‘96, ‘00, ‘04, ’08 & ‘12

James Tomkins - Rowing ‘88, ‘92, ‘96, ‘00, ’04 & ‘08

Olympians

Australian

Olympians Association

ACT Events

Bubbles and Floss · March 2022

Family Christmas Day · November 2022

NSW Events

Get Together · September 2022

QLD Events

Annual Dinner · October 2022

Christmas celebration · December 2022

WA events

Networking Luncheon hosted by Westarmers · August 2022

Christmas lunch · november 2022

SA Events

Networking Lunch hosted by WRP Legal and Advisory · August 2022

Annual Dinner · november 2022

Olympians

Olympians' Births

From Athlete to Parent: Celebrating Australian Olympians Who Became Parents

In the past year, eight Australian Olympians have welcomed new additions to their families, balancing the demands of elite athletic training with the joys and challenges of parenthood. Their stories inspire us all to pursue our passions, even in the face of adversity. Congratulations to these amazing athletes on their remarkable achievements both as athletes and parents.

Lyndsie Krishnamoorthy (née Fogarty)

Lucinda Whitty

Lyndsie Krishnamoorthy

Lavinia Chrystal

Erika Yamasaki

Bernadette Wallace

Ben St Lawrence

Olympians

Olympians IN Memoriam

Remembering the Legacy: Honoring the Lives and Achievements of past olympians

William (Cliff) Sander

9 February 2022

Queensland

John Landy

24 February 2022

Victoria

1956 Melbourne

Dean Woods

3 March 2022

Victoria / Queensland

1988 Seoul

1996 Atlanta

Reg Marsh

2 April 2022

New South Wales

1968 Mexico City

Sandra Pisani

17 April 2022

South Australia

1988 Seoul

Inga Freidenfelds

9 April 2022

South Australia

Jack Trickey

1 April 2022

South Australia

Arthur Winther

16 April 2022

New Zealand

Geza Varasdi

4 May 2022

Hungarian Immigrant Victoria

1956 Melbourne

David Forbes

21 May 2022

New South Wales

1972 Munich

1976 Montreal

Gary Winram

29 May 2022

Queensland

John Rigby

13 June 2022

Queensland

Edmond Brooks

1 July 2022

Western Australia

Sean Quilty

16 July 2022

Victoria

Shirley Cotton

11 July 2022

New South Wales

William Berge-Phillips

26 July 2022

New South Wales

Terry Davies

31 July 2022

Victoria

1964 Tokyo

Doug Donoghue

1 August 2022

New South Wales

Robert (Bobby) Lay

5 August 2022

Victoria

Robert Dauer

24 August 2021

Victoria

Barbara Cunningham

22 August 2022

Victoria

Allan Wood

10 October 2022

Queensland